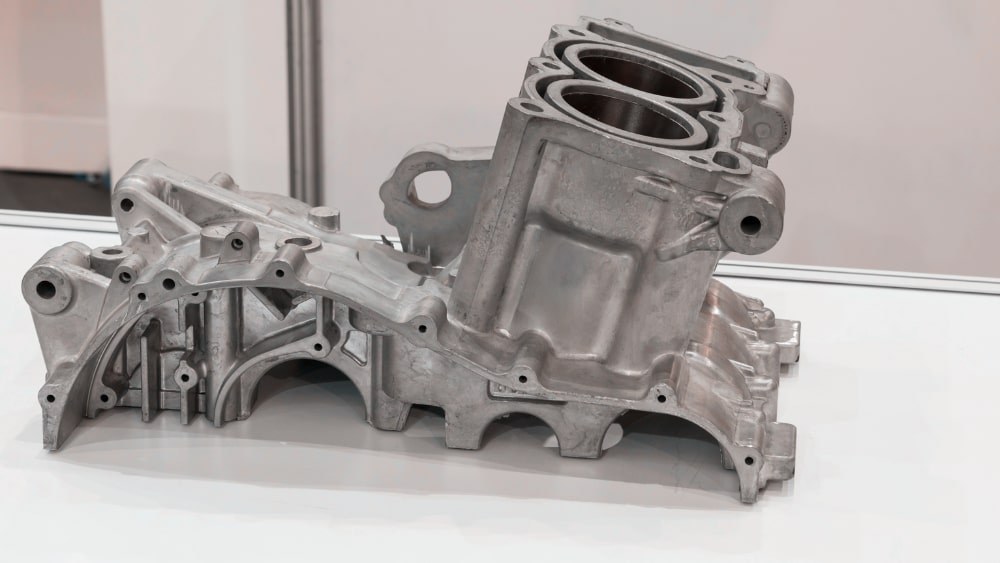

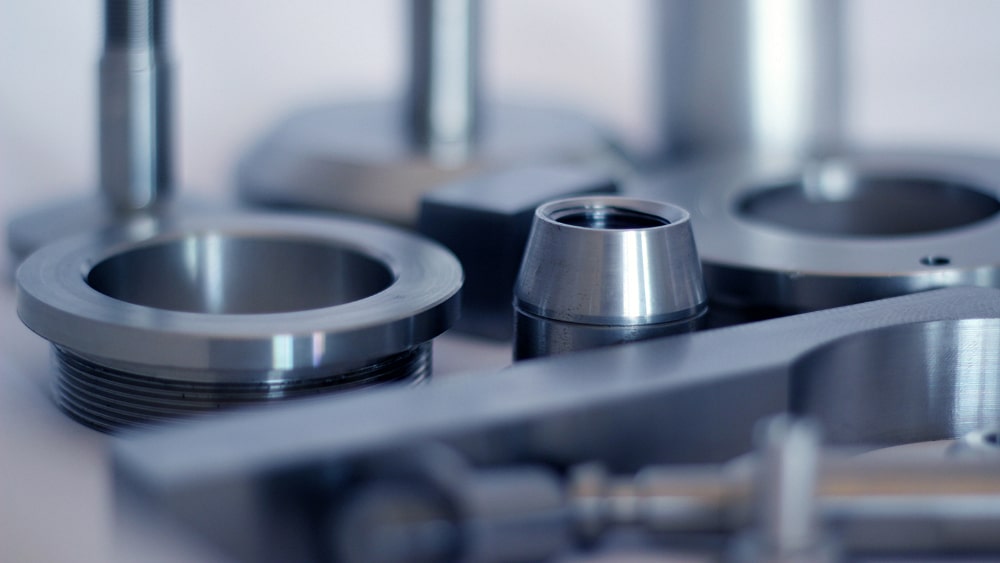

Understanding common casting defects, including low-pressure casting defects, shrinkage cavities, cold shuts, cracks, and sand adhesion, is crucial for engineers and manufacturers aiming to improve casting quality and reduce scrap rates.

This guide provides a comprehensive overview of the formation mechanisms, characteristics, and preventative measures for various casting defects, with a focus on complex thin-walled aluminum castings and other precision components. By following these guidelines, manufacturers can optimize mold design, control molten metal flow, and implement effective feeding and venting strategies to obtain defect-free castings.

Table of Contents

- Gas Porosity

- Shrinkage Cavities and Shrinkage Porosity

- Inclusions

- Cold Shut and Misrun

- Cracks

- Sand Adhesion

- Deformation

- Flash and Burrs

- Leakage

- Conclusion

1. Gas Porosity

1.1 Characteristics

(1) Gas Porosity

Gas porosity refers to cavity-type defects formed by gas inside a casting. The internal surfaces of the pores are generally smooth, and their shapes are mainly pear-shaped, spherical, or elliptical. These pores usually do not appear on the casting surface. Large pores often exist individually, while small pores usually occur in clusters. For aluminum components, such as lost foam casting parts, gas porosity is a common quality concern.

(2) Subsurface Gas Porosity

Shrinkage defects form when molten metal fails to feed the casting properly during solidification, resulting in voids such as shrinkage cavities, porosity, looseness, shrinkage depressions, and sinking. These defects are common in complex aluminum components, including stainless steel castings and aluminum alloys. Effective feeding design and controlled solidification can reduce these defects.

(3) Gas Cavities (Surface Gas Pits)

These are gas pores that appear as relatively smooth concave depressions on the surface of the casting.

(4) Gas–Shrinkage Porosity

This defect is formed by the combination of dispersed gas porosity with shrinkage cavities or shrinkage porosity.

(5) Pinholes

Pinholes are precipitation-type gas pores, generally needle-head sized, distributed across the casting cross-section. This type of porosity commonly appears in aluminum alloy castings and causes severe deterioration of casting performance.

① Spot-Type Pinholes

Under low-magnification microstructure observation, these pinholes appear as discrete round spots with clear outlines and no interconnection. The number of pinholes per square centimeter can be counted, and their diameters can be measured. This type of pinhole is easily distinguished from shrinkage cavities and shrinkage porosity. Spot-type pinholes are formed by gas bubbles precipitated during solidification and mostly occur in castings with a narrow solidification temperature range and good feeding capability, such as ZL102 alloy castings. When the solidification rate is relatively fast, spot-type pinholes may also appear in ZL105 alloy castings whose composition is far from the eutectic.

② Network-Type Pinholes

Under low magnification, these pinholes appear as densely interconnected networks, accompanied by a small number of larger pores. The number of pinholes is difficult to count, and their diameters are hard to measure. They often exhibit terminal branches and are commonly referred to as “fly-leg” structures. In alloys with a wide solidification temperature range, gas precipitated during slow solidification is distributed along grain boundaries and within well-developed interdendritic spaces. At this stage, the solidification skeleton has formed, feeding channels are blocked, and network-type pinholes form along grain boundaries and interdendritic regions.

③ Mixed-Type Pinholes

This type consists of a mixture of spot-type and network-type pinholes and is commonly found in castings with complex structures and uneven wall thickness.

Pinholes are classified into grades according to national standards. The poorer the pinhole grade, the lower the mechanical properties of the casting, as well as reduced corrosion resistance and surface quality. If the pinhole grade exceeds the allowable limit specified in the casting technical requirements, the casting must be scrapped. Among these, network-type pinholes are more harmful than spot-type pinholes because they severely disrupt the alloy matrix.

(6) Surface Pinholes

Surface pinholes are dispersed gas pores clustered in the surface layer of the casting. Their characteristics and formation mechanisms are the same as those of subsurface gas porosity. These defects are usually exposed on the casting surface and can be removed by machining 1–2 mm.

(7) Gas Boiling (Blowholes)

During pouring, a large amount of gas generated cannot be discharged smoothly and causes boiling within the molten metal, resulting in a large number of gas pores inside the casting, or even incomplete casting defects.

1.2 Classification of Gas Porosity

(1) Precipitation Porosity

This type of porosity is uniformly distributed in high-temperature regions inside the casting, such as near gates, risers, and hot spots. The pores are fine and dispersed and often coexist with shrinkage cavities. “Precipitation” refers to gas dissolved in molten aluminum that is not completely removed and precipitates during solidification.

(2) Reaction Porosity

This type of porosity is uniformly distributed along the contact surface between the mold wall and the casting. The pore surfaces are smooth and may appear silver-white (in steel castings), metallic bright, or dark. “Reaction” refers to gases generated by chemical reactions between molten aluminum and materials in molds, cores, chills, or coatings.

(3) Entrapped (Invasive) Porosity

This type of porosity is mainly distributed in the upper part of the casting, with large and smooth pores. “Entrapment” refers to gas in the mold cavity that fails to be discharged outside the mold in time and intrudes into the casting.

1.3 Formation Mechanism of Gas Porosity

In low-pressure casting, the mold is basically sealed, and molten metal fills the cavity rapidly. Gas cannot escape in time and becomes trapped in the casting, forming gas porosity or pinholes.

(1) Precipitation of Dissolved Gas from Molten Metal

This results in precipitation porosity (pinholes). Gas dissolved during metal melting precipitates as gas solubility decreases during cooling and solidification. If the gas cannot be discharged in time, gas porosity forms in the casting. This is aggravated by high gas content in molten aluminum, high inclusion content, poor refining effectiveness, and slow solidification rates.

(2) Gas Generated by Heated Wet Cores, Coatings, or Contaminated Chills

This leads to reaction porosity (subsurface gas porosity). Gas pores are generated by chemical reactions between mold materials and molten metal, or reactions occurring within the molten metal itself.

(3) Gas Trapped in the Mold Cavity

This results in entrapped porosity (single large gas pores). Causes include unreasonable casting process design, poor venting of molds or cores, or improper operation such as blocking vents during pouring (excessively fast pouring speed), which traps gas inside the casting.

1.4 Preventive and Control Measures

(1) Strictly Follow Melting Operation Procedures to Prevent Precipitation Porosity

① Raw materials and return scrap must be dry, free of rust, oil, and contaminants, and must be preheated before use.

② Melting temperature should not be excessively high. The higher the melting temperature, the greater the amount of gas (mainly hydrogen) dissolved in the molten metal. Therefore, melting temperature must be strictly controlled, especially for non-ferrous alloys.

③ The melting time of any metal should be minimized to prevent excessive gas absorption caused by prolonged melting.

④ Aluminum-containing alloys should preferably not be melted in power-frequency induction furnaces, as these furnaces have strong stirring effects. Aluminum easily oxidizes to Al₂O₃ when exposed to air, which enters the molten metal as slag and promotes gas precipitation. In addition, aluminum readily reacts with H₂O, causing hydrogen absorption. Resistance furnaces, far-infrared heating furnaces, or fuel-fired reverberatory furnaces are recommended alternatives.

⑤ During charging, materials with lower melting points should be added first, followed by materials with higher melting points. This reduces gas absorption by minimizing contact area and contact time between the charge and air.

⑥ After degassing, slag should be skimmed immediately and pouring should proceed without delay to prevent reabsorption of gas.

⑦ Degassing can be carried out using hexachloroethane tablets, argon gas refining, or vacuum degassing.

(2) Minimize Gas Generation from Coatings, Sand Cores, and Metal Molds to Prevent Reaction Porosity

① Select appropriate coatings with low gas evolution and adequate permeability.

② Molds and cores should be preheated before coating. After coating, they must be thoroughly dried before use.

③ Coating surfaces should not be smoothed after spraying. Any area where coating peels off must be repaired immediately.

④ Sand cores must be completely dried before use.

⑤ Metal molds and chills must have smooth, clean surfaces and be thoroughly dried before use.

(3) Improve Venting Conditions of Molds and Cores

Based on casting characteristics and filling behavior, select appropriate venting locations and methods, such as vent grooves, vent strips, vent needles, vent plugs, and vent holes.

(4) Select an Appropriate Filling Speed

Ensure smooth and stable filling of molten metal to prevent air entrapment. The recommended molten metal rising speed is generally controlled at approximately 50 mm/s. This corresponds to proper gravity casting practice, including control of pouring temperature, mold temperature, pouring speed, and pouring time.

2. Shrinkage Cavities and Shrinkage Porosity

Shrinkage defects are defects formed during metal solidification shrinkage when molten metal fails to effectively feed the casting. These defects include shrinkage cavities, shrinkage porosity, looseness, shrinkage depressions, and shrinkage sinking.

2.1 Characteristics

① Shrinkage Cavities

Shrinkage cavities are irregularly shaped holes in castings with rough internal walls and dendritic crystals. These defects usually occur in the last solidified regions of the casting.

② Shrinkage Porosity

Shrinkage porosity consists of dispersed and fine shrinkage cavities visible on the casting cross-section, sometimes requiring a magnifying glass for observation. For example, when producing aluminum pistons by low-pressure casting, shrinkage porosity may sometimes appear at the piston crown.

③ Looseness

Looseness refers to very fine pores formed in regions where the casting solidifies slowly. These pores are distributed within dendrites and between dendrites. It is a mixed defect composed of dispersed gas porosity, microscopic shrinkage porosity, and coarse microstructure, which reduces casting density and easily causes leakage.

④ Shrinkage Depression

Shrinkage depression is the collapse or sinking phenomenon occurring on the flat surface at the junction of thick sections or cross-sectional intersections of the casting. Shrinkage cavities may sometimes exist beneath the depression, and shrinkage depressions may also appear near internal shrinkage cavities.

⑤ Shrinkage Sinking

Shrinkage sinking is a casting defect that occurs when using water-glass limestone sand molds. Its characteristic feature is the expansion of casting cross-sectional dimensions.

⑥ Shrinkage Cracking

Shrinkage cracking refers to cracks caused by improper feeding, restrained shrinkage, or uneven shrinkage of the casting. These cracks may occur immediately after solidification or at lower temperatures.

2.2 Causes

Shrinkage cavities and shrinkage porosity are formed because, during solidification, molten metal undergoes liquid shrinkage and solidification shrinkage, resulting in volume contraction. When this volume deficit is not compensated by effective feeding, cavities tend to form in the last solidified regions of the casting.

Unlike conventional gravity casting, low-pressure casting fills the mold cavity from bottom to top, with the gate located at the lower part. To ensure sufficient feeding, a top-down directional solidification pattern must be established, meaning that regions farther from the gate should solidify first, and the gate region should solidify last. Otherwise, shrinkage cavities and shrinkage porosity will occur.

2.3 Preventive Measures (Simultaneous Solidification or Directional Solidification)

Since low-pressure casting and differential-pressure casting are both counter-gravity casting processes, gravity constantly interferes with feeding. Therefore, regardless of whether sand molds or metal molds are used, and regardless of whether the casting adopts simultaneous solidification or directional solidification, the quality of the molten metal surface pressurization control system is the key factor determining casting density.

This is especially critical for thin-walled castings produced in metal molds, where the solidification time is inherently short. When the molten metal fills to the top of the mold, the fraction of solid phase in the molten metal has already reached a considerable level. At this moment, pressure must be increased rapidly to overcome the adverse effect of gravity and achieve effective feeding. This is a decisive moment for casting density.

At present, some molten metal surface pressurization control systems still increase pressure slowly according to the filling speed at this critical moment. Others perform even worse: they can increase pressure normally at low pressure levels, but as pressure increases, the pressurization rate becomes slower. This phenomenon is known as a downward-opening parabolic filling curve.

When the molten metal has almost completely solidified, the control system finally raises the pressure for feeding compensation. Obviously, this is too late and cannot effectively improve casting density. In production, the feeding pressure may already be very high (up to 0.2 MPa), yet shrinkage porosity still exists, resulting in an excessively high pressure-leakage failure rate.

When the feeding channel is reasonable, the main cause of this problem is improper timing of pressure increase by the control system, rather than the mistaken belief that “feeding pressure magnitude has little effect on casting density.” For example, a factory trial-produced a large thin-walled casting for more than two years without obtaining qualified products. The main issues were severe shrinkage porosity, poor density, and serious pressure leakage.

After replacing the old molten metal surface pressurization control system with a closed-loop feedback “CLP-3” type low-pressure casting molten metal surface pressurization control system, the situation changed dramatically. Without major changes to the original process, qualified castings were successfully produced.

In another case, a factory in Shenyang used a manual control system on a differential-pressure casting machine to produce thin-walled shell castings, with a scrap rate as high as 80%–90%. After switching to the “CLP” type differential-pressure casting molten metal surface pressurization control system designed by Harbin Institute of Technology, the scrap rate dropped sharply, and qualified castings with clear edges and fully formed lettering were produced.

These examples demonstrate that molten metal surface pressurization control systems play an extremely important role in differential-pressure casting and low-pressure casting.

Specific preventive measures for eliminating shrinkage cavities occurring during directional solidification in metal molds are as follows:

(1) Ensure a reasonable mold temperature distribution, with lower temperature at the upper part and higher temperature at the lower part. It is preferable to use the CLP-5 type molten metal surface suspension pressurization control system, which can increase the lower mold temperature and enhance feeding capacity.

(2) Ensure a reasonable distribution of the mold’s thermal capacity, with smaller thermal capacity at the lower part and larger thermal capacity at the upper part (i.e., thinner mold walls at the bottom and thicker mold walls at the top).

(3) Apply forced cooling at local hot spots to adjust the temperature field to one that is favorable for feeding.

(4) For local “cold spots” that hinder feeding, drill holes or mill grooves around the backside and fill them with insulating materials to increase thermal resistance and obtain a reasonable temperature field.

(5) Reduce filling speed and mold temperature appropriately, but not excessively, to avoid cold shuts or misruns.

(6) Appropriately lowering the pouring temperature has a significant effect on reducing shrinkage porosity.

For shrinkage cavities and shrinkage porosity under simultaneous solidification, the elimination methods include ensuring a reasonable mold temperature distribution with higher temperature at the upper part and lower temperature at the lower part; ensuring a reasonable mold thermal capacity distribution with smaller thermal capacity at the upper part and larger thermal capacity at the lower part (i.e., thinner mold walls at the top and thicker mold walls at the bottom). The treatment methods for local hot spots and cold spots are the same as described above.

(4) The control methods for mold temperature, filling speed, and pouring temperature are opposite to those used for directional solidification.

For sand mold casting, process modifications are relatively convenient. Therefore, whether simultaneous solidification or directional solidification is adopted, there are many methods to eliminate shrinkage cavities. The specific preventive measures are as follows:

(1) For large and medium-sized non-ferrous alloy and ferrous metal castings with large wall thickness differences, risers should be set up, and pressure feeding from risers should be applied to enhance feeding and prevent shrinkage cavities and shrinkage porosity.

(2) Appropriately reduce pouring temperature or pouring speed.

(3) Rationally design the casting process to establish conditions for directional solidification or simultaneous solidification.

3. Inclusions

3.1 Characteristics

(1) Inclusion-Type Defects

Inclusion-type defects are a general term for various metallic and non-metallic inclusions present in castings. These inclusions are usually oxides, sulfides, silicates, and other impurity particles that are mechanically retained in solid metal, formed within the metal during solidification, or generated through reactions occurring after solidification. Such defects include inclusions, cold shots, internal cold shots, slag inclusions, and sand holes.

(2) Inclusions

Inclusions are particles within the casting or on its surface that have a chemical composition different from that of the base metal. These include slag, sand, coating layers, oxides, sulfides, silicates, and similar substances.

(3) Endogenous Inclusions

Endogenous inclusions are formed during melting, pouring, and solidification due to chemical reactions between molten metal and furnace gases (and sometimes the mold). They may also form when the temperature of molten metal decreases, causing a reduction in solubility and subsequent precipitation of inclusions.

(4) Exogenous Inclusions

Exogenous inclusions are caused by slag and externally introduced impurities.

(5) Slag Inclusions

Slag inclusions are inclusion-type defects caused by molten metal that is not clean, or by improper pouring methods and gating system design. They are formed by slag, low-melting-point compounds, and oxides entrapped in the molten metal. Because their melting point and density are generally lower than those of molten metal, they are usually distributed on the top surface or upper regions of the casting, as well as on the lower surfaces of cores and in dead corners of the casting. The fracture surface lacks metallic luster and appears dark gray.

(6) Coating Slag Pits

These are irregular pits containing residual coating deposits left on the casting surface due to powdering or peeling of the coating layer. Coatings may detach from pouring tools, molds, riser tubes, and sand cores. In particular, when sand cores are brushed with coating and then ignited with flame for drying, peeling or blistering often occurs. Therefore, when production schedules allow, sand cores should preferably be dried in a constant-temperature oven.

(7) Cold Shots

Cold shots are metallic particles or beads found on the surface of a casting below the pouring location. Their chemical composition is the same as that of the casting, and oxidation is present on their surfaces. They are generally formed by splashing of molten metal, where small amounts of metal rapidly solidify upon contacting the mold and fail to fuse with subsequently poured molten metal.

(8) Sand Holes

Sand holes are cavities within or on the surface of a casting that contain sand particles.

(9) Hard Spots

Hard spots are dispersed or relatively large hard inclusions that appear on the fracture surface of a casting. They are most often discovered during machining or surface treatment.

(10) Slag–Gas Porosity

Slag–gas porosity refers to non-metallic inclusions located on the upper surface near the pouring position of the casting. These defects are usually found after machining and coexist with gas porosity. The pore sizes vary and often appear in clustered distributions.

3.2 Causes

Oxide slag inclusions frequently occur in low-pressure castings. Analysis of their sources indicates the following causes:

(1) During continuous production, when molten aluminum is replenished into the crucible, oxide slag on the liquid surface may be flushed into the riser tube and subsequently carried into the mold during pouring. Therefore, after replenishing molten aluminum, a tool should be inserted from the upper end of the riser tube to scoop out slag inside the tube.

(2) Oxide films formed due to repeated rising and falling of the molten metal level in the riser tube.

(3) Excessively rapid pressurization, which causes splashing and the formation of oxide films.

In addition, non-metallic inclusions may also be caused by the detachment of mold materials and coatings.

3.3 Preventive and Control Measures

(1) Strictly control the filling speed to ensure that molten metal rises smoothly without impact or splashing.

(2) Thoroughly remove oxide slag from the molten alloy.

(3) Install filters at the riser tube inlet or within the gating system inside the mold. However, filters are not suitable for all products. For some large, complex castings with thin walls and heavy weight, the use of filters may result in incomplete filling. Filters are more suitable for small, simple castings with thicker walls and lighter weight.

(4) Check whether the coating layer has peeled off, and thoroughly clean dust, sand particles, and debris from the mold cavity.

4. Cold Shut and Misrun

4.1 Characteristics

(1) Cold Shut

A cold shut is a defect characterized by penetrating or non-penetrating seams in a casting, with rounded edges. The seams are often separated by oxide films and fail to fully fuse into a single, continuous body. Cold shuts commonly occur on wide upper surfaces far from the gate, in thin-walled sections, at locations where molten metal streams converge, and at chilled areas such as chill blocks and core supports.

(2) Misrun

Misrun refers to a casting defect in which the casting is incomplete, has an incomplete contour, or may appear complete but exhibits rounded and smooth edges and corners. This defect commonly occurs in regions far from the gate and in thin-walled sections. It is related to the gating and pouring system.

4.2 Formation Causes (Fluidity and Venting)

(1) Low mold temperature or low molten metal temperature;

(2) Low filling pressure of molten metal or slow filling speed;

(3) Poor venting of the mold cavity, resulting in excessive back pressure of gas inside the cavity.

4.3 Preventive Measures (Fluidity and Venting)

(1) Adopt appropriate mold temperatures and molten metal pouring temperatures (two critical process parameters). In general, for ordinary castings, thin-walled complex castings, metal cores, and metal molds, typical mold temperature ranges are approximately 200–300 °C, 250–320 °C, and 250–350 °C, respectively. The pouring temperature for low-pressure casting is usually 10–20 °C lower than that for gravity casting under the same conditions.

(2) Use reasonable pressurization specifications.

(3) Improve venting conditions and venting methods of molds and cores.

(4) If very shallow flow or convection marks are found on the casting surface, they can usually be eliminated by applying a small amount of coating to the corresponding flow-convergence area of the mold.

5. Cracks

5.1 Formation Causes

Cracks can be classified into hot cracks and cold cracks. During the cooling and solidification of molten metal, stresses are generated for various reasons. If these stresses occur shortly after the solid-phase skeleton has just formed, the resulting cracks are referred to as hot cracks. Conversely, cracks formed at a later stage are referred to as cold cracks.

5.2 Preventive Methods

(1) Increase the collapsibility of molds and cores in areas that hinder shrinkage, and increase the thickness of the coating.

(2) Enhance feeding to areas prone to hot cracking. Since hot cracks mostly occur in regions that solidify last, strengthening feeding in these areas will naturally reduce the occurrence of hot cracks.

(3) Increase the heat dissipation capability of the mold in hot-crack-prone areas, which may cause the hot cracking location to shift or prevent hot cracking altogether.

(4) Machine shallow grooves parallel to the crack direction on both sides of the corresponding metal mold (or core) at the crack location. This helps disperse shrinkage stress during solidification and achieve the purpose of preventing hot cracks.

(5) Opening the mold and removing the casting as early as possible can effectively reduce hot cracking.

(6) Increasing mold temperature and pouring temperature is beneficial to simultaneous solidification and has a positive effect on reducing hot cracks.

For cold cracks, preventive measures can be considered during structural design. In addition, newly produced castings can be subjected immediately to slow cooling or annealing treatment, which helps reduce residual thermal stress and effectively decreases the occurrence of cold cracks. Reinforcing ribs can also be added to the component design to prevent cracking.

6. Sand Adhesion

6.1 Formation Causes

Sand adhesion can be classified into chemical sand adhesion and mechanical sand adhesion. However, in low-pressure casting and differential-pressure casting, mechanical sand adhesion is the primary type. This defect occurs because, during the pressure-holding stage, the applied pressure increases significantly. This pressure forces the molten metal to overcome surface tension and penetrate into the interior of the sand mold or sand core, thereby causing mechanical sand adhesion.

6.2 Preventive Methods

(1) Apply a dense coating layer with high refractoriness to the surface of the sand mold or sand core. This method is highly effective in preventing sand adhesion defects.

(2) Appropriately reduce the pouring temperature.

(3) Appropriately reduce the pressure increment during the pressure-holding stage.

7. Deformation

7.1 Formation Causes

The causes of casting deformation are the same as those of cold cracking.

7.2 Preventive Methods

The methods for addressing this issue are basically the same as those used for cold cracking. In addition, several specific measures can be applied:

(1) According to the deformation characteristics of the casting, a counter-deformation correction allowance should be reserved in the mold design.

(2) Reinforcing ribs should be reserved in the mold and removed after heat treatment and annealing.

(3) After deformation occurs, the casting can be corrected using a press.

8. Flash and Burrs

8.1 Formation Causes

Flash and burrs are caused when the mold does not close properly due to thermal stress deformation or other mechanical reasons (e.g., insufficient hydraulic cylinder pressure), resulting in gaps. After filling, these gaps leave flash and burrs on the casting.

8.2 Preventive Methods

(1) Increase the stiffness of the mold and modify the mold structure to reduce thermal deformation of the mold.

(2) Flash or burrs may also be caused by operational errors, such as deformation (impact) at mold corners, resulting in protrusions on one side of the parting surface. Careful inspection or testing on a platform is recommended, and any protrusions can be filed down.

(3) Appropriately reduce pouring temperature and pouring speed (filling speed, pressurization speed), or extend the pressurization delay time to allow solidification of the skin.

9. Leakage

Leakage refers to the occurrence of air, water, or oil seepage in a casting during airtightness testing or service. High-density aluminum castings often experience leakage issues under pressurization tests. These problems are usually caused by defects such as gas pores, shrinkage cavities, porosity, coarse microstructure, or cracks, where large amounts of Al₂O₃ are present.

The primary reason for leakage is that during pouring, molten aluminum comes into contact with air, and an oxide film immediately forms on its surface. During mold filling, turbulent flow caused by uneven metal flow can trap these oxide films along with absorbed gases into the aluminum melt. The relative density of these inclusions is close to that of the aluminum melt, and as the melt viscosity increases with decreasing temperature, the impurities fail to float out and remain inside the casting. Adjacent oxide films provide sites and opportunities for initial crack formation. Additionally, gas released during solidification and insufficient feeding can produce micro-porosity and micro-shrinkage in these areas.

These defects significantly reduce the mechanical properties of the material and are the root cause of leakage under pressure. Therefore, the filling speed of molten metal into the mold cavity and the smoothness of the flow are critical factors. Studies abroad have shown that when filling a 5 mm thick plate at different speeds, the resulting casting exhibits different strength and ductility. Even at the same filling speed, turbulence severity caused by mold cavity structure differences results in variations in strength and ductility at corresponding locations.

Hence, the hydraulic pressurization control system has a crucial impact on the quality of complex thin-walled castings that require high internal integrity.

Conclusion

In summary, understanding and controlling casting defects—such as porosity, shrinkage, inclusions, cold shut, misrun, cracks, sand adhesion, flash, burrs, deformation, and leakage—is critical for ensuring the mechanical performance, dimensional accuracy, and overall quality of metal castings. Each defect has specific formation mechanisms and preventive measures, which, when properly applied, can significantly improve casting integrity and reduce the risk of failures in service.

For manufacturers and engineers seeking high-quality, custom metal solutions, Qianhao offers professional metal customization services. With advanced production capabilities, strict quality control, and expertise across a wide range of alloys and casting techniques, Qianhao can provide tailored solutions that meet precise specifications and performance requirements. Whether you need prototyping, small-batch production, or large-scale supply, Qianhao’s metal customization services ensure reliable, high-performance castings for your applications.